Unless you’re interested in reading why I like fast film, you can skip to this section for how I actually develop it. That’s the part that covers what made me want to write this in the first place. I kept losing my notes so this will actually serve as a long-winded note-to-self.

If you want to skip to some pictures, see results.

Historical context Link to heading

Around 2007, I got pretty into photography. Got a Nikon D50 and that felt pretty cool. My first camera! A digital SLR! I still have that thing.

I really loved the idea of shooting film but it was tough to find and processing was very expensive in my province. It was around the point where film had very clearly ’lost’ to digital and the professional market had moved on. Kitting out a 35mm camera kind of felt like the wrong thing to do.

There was a couple of photographers in my province who didn’t mind all that. They were shooting film, being experimental, getting great results. Sketchy bathroom darkrooms, old rangefinders, expired film, ebay all the things. At that time, everyone was talking about the 12mp APS-C Nikon D300. Kodak and Fuji had been discontinuing a lot of their heavy hitting film stocks. Leaning into film was weird!

One of the fellas I followed on Flickr was pushing black and white film and doing a damn good job of it. I didn’t understand it much but it intrigued me and it stuck with me. I wanted to do what they were doing. So with the pandy in full swing and my usual hobbies out the window, I needed something I could do as far away from people as possible. It was time to shoot some film.

Back to basics: film speed Link to heading

I’ll assume you understand how exposing a photograph works (shutter speed, aperture, ISO) but let’s do a quick aside about film speed.

Every film has an ISO sensitivity number that indicates the ‘speed’ of the film. That is, how sensitive the film is and thus how fast it can collect light. This is sometimes referred to as the Exposure Index or EI. I think they’re practically interchangeable but don’t quote me on that.

Lower ISO numbers represent slower film speeds, higher numbers are faster. Film ISOs at 50 or 100 are generally used in bright sunlight or with a tripod or flash. If shooting indoors with available light, 800 might be handy to make the most of what you have.

It’s very important to note that the slower the film, the finer the film grain. So while a 1600 speed film might be easier to shoot hand-held, it will also have a much more pronounced grain than something at 100.

Let’s use Ilford HP5 for the sake of an example. That has an ISO of 400. When you load HP5, you tell the meter that it’s an ISO 400 film (the camera might figure it out for itself). It’ll calibrate the measurements of light levels accordingly and you’re ready to go for a shoot!

Film speed and development Link to heading

Once you’re done the roll, you grab your handy technical information sheet for Ilford HP5. A simplified one is printed on the inside of the box the film came in. Find the table of development times table, find the row that corresponds to your chemical choice, and look for the column that corresponds to the ISO number on the box. That’ll lead you to a duration in minutes. This duration is how long you develop HP5 with that particular chemical at that particular ISO number. For HP5 @ 400, using DD-X, at 20 degrees C, you’re looking at 9 minutes. Simple, right? Clear as mud?

The idea is to match the number on the box, the number your camera thought you were shooting, and the column in the technical info sheet to end up with pictures that look more or less how the film was intended to look. And this gives you great results indeed. This is how most film is shot and developed.

Pushing film Link to heading

So what’s it mean to “push” film? Well there are some hints in the technical information sheet. There are a bunch of columns with different numbers. 400, 800, 1600, 3200, most with their own durations!

You’re “pushing” film when you ignore the number on the box, pick a higher number, and treat the film that way through the whole process. Keeping with the Ilford HP5 example, let’s pick 1600. You’d tell your meter that you’ve loaded a 1600 speed film, shoot happily, and then develop the film for a longer period of time afterward. Rather than 9 minutes, now you’re looking at 13.

When you do this, your meter is calibrated to underexpose the film since it thinks the film is faster than it really is. You are making up for that by letting it sit in the developer for a longer time.

This works because film, particularly black and white film, has such a wide exposure latitude. This is the extent to which film can be overexposed or underexposed and still achieve a ‘good’ result. Black and white film is especially forgiving when your definition of ‘good’ has some wiggle room.

FWIW you can also pull film but we’ll stick to pushing for this post.

OK why do that? Link to heading

Pushing film can be very useful. Say you have a bunch of Ilford HP5 and you know you’ll be taking photos of a band at a dark club. Shutter speeds at ISO 400, even with a very fast lens, might not be quick enough to capture the scene the way you want. You decide to push the film to 1600 and now you can use quicker shutter speeds! Sweet.

Pushed film also has a vibe. This is what I was getting at when I said the definition of ‘good result’ needs some wiggle room. You’ll generally get much deeper shadows and ‘richer’ dark tones. Most notable is the grain. It has great texture but can get pretty extreme. I think it can look kind of spooky and moody.

I think the vibe is what caught my attention but the idea of shooting in really low light was the kicker. A whole world of photography existed that I had never entered. One without tripods and reciprocity failure.

Enter Delta 3200 Link to heading

Sure I could have tinkered with HP5 at 1600 but I wanted night vision. Thankfully, Ilford make a film called Delta 3200. As you likely gleaned from the name, it’s an ISO 3200 film. It’s grainy and low-contrast but it is tied for being the fastest available black and white films so that sounds like a good starting point. Ilford bill it as being “Ideal for fast action and low light photography.” I’m sure this is true straight out of the box but, again, I wanted night vision. Grain be damned. So I bought myself some Delta 3200 and decided I’d push it to 12500.

My process Link to heading

I use a Nikon F6 which doesn’t natively support ISO values over 6400. I tell the camera that I’m shooting at 6400 and set the meter to underexpose by a a full stop.

Once the film is done, it’s time for my sketchy kitchen-table darkroom. All of the light-sensitive steps happen in a wacky black bag with two arm holes. This thing gets really warm pretty quickly so practising getting an old strip of film onto the reel in advance is essential.

The developer I use is DD-X and I try to do everything around 20 degrees C. I don’t actually make any attempt to be accurate with the temps which may be an issue. The room I store my chemicals in is actually a little cold. I will make note to be more careful here for potentially better results. I use ILFOSTOP and Ilford’s rapid fixer for everything B&W. I use Photo-Flo 200 for a wetting agent with all of my film to help it dry. Works very similar to the drying helper you put in a dishwasher.

I do two rolls at a time with a Paterson two-reel tank requiring 600ml of working solution.

| Chemical | Dilution | Concentrate (ml) | Water (ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DD-X | 1:4 | 120 | 480 |

| Ilfostop | 1:19 | 30 | 570 |

| Fixer | 1:5 | 100 | 500 |

For agitation, I invert the tank up and back again about 5 times in a 10s agitation. No wild shaking. It’s not a paint can. When laying the tank back down, I give it a few light taps on the work surface to loosen any bubbles.

| Step | Time | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DD-X | 18 mins | Agitate for 10s every 60s |

| Stop bath | 20 seconds | Agitate the entire time |

| Fixer | 4 minutes | Agitate for 10s every 60s |

| Wash 1 | - | Fill with tap water, invert 5 times |

| Wash 2 | - | Fill, invert 10 times |

| Wash 3 | - | Fill, invert 20 times |

| Wash 4 | - | Fill, add Photo-Flo, invert 5 times |

I shake my film out while it’s still on the reel. I don’t know if this does anything but it makes me feel better.

I don’t use an actual squeegee on my film but I do use my fingers to lightly ‘squeegee’ off any extra water.

I might change my dev time to 19 minutes. I don’t think it’ll make a massive difference but I feel like my last roll was a tad underdone. Cold chemicals might have also contributed to it feeling a little off.

I might try 25000 next. If I do, I’ll write another (much shorter) post for that.

Results Link to heading

Check out Flickr to see more examples in higher res.

All of these were shot on Delta 3200, pushed to 12500 as above.

In most cases, these were scanned by a Nikon D850 with a 60mm macro lens but some were done through a Plustek OpticFilm 8200i. They were all processed in Adobe Lightroom Classic with Negative Lab Pro. I could probably do another post about my scanning and developing workflow. Maybe I’ll write it out some day.

Anyway that’s it.

Boots by a fire Link to heading

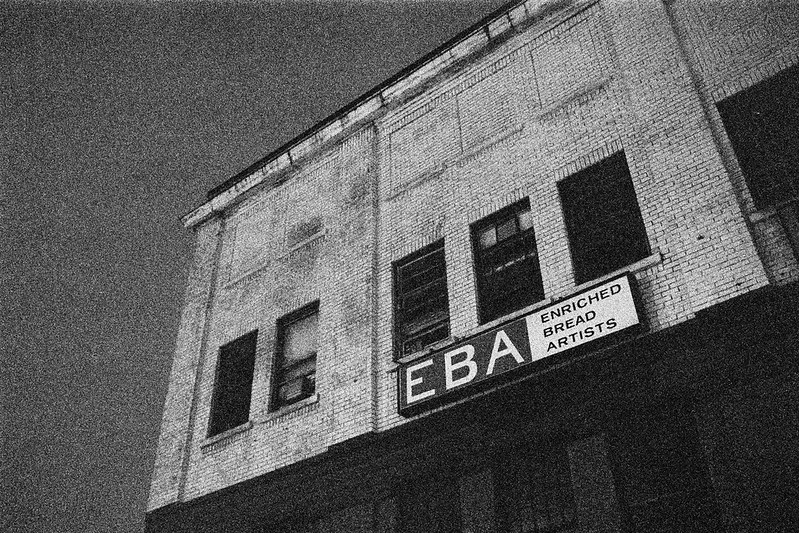

EBA at night Link to heading

Some stairs in my neighbourhood Link to heading

A tunnel in my home town Link to heading